Alkyds offer a shorter drying time than oils and a capacity for

multiple glazes, two qualities that benefit my paintings.

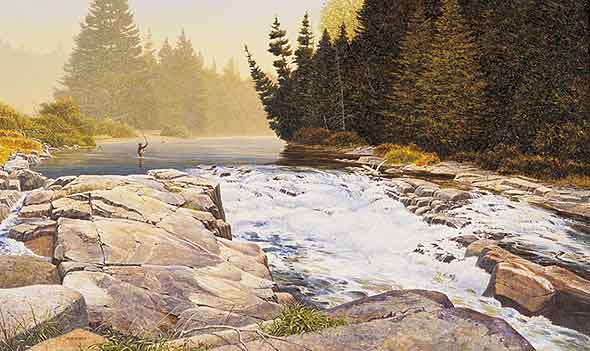

Fishing The Ausable, 1992, alkyd on masonite, 14 x 25. I used multiple glazes in the background behind the fisherman to lighten and loosen the definition in that area. This effect melts the background into the atmosphere and contrasts it to the sharply defined and darker foreground.

Twenty-three years ago, I first started working in the alkyd medium.

At that time, I was looking for a medium that did not dry as quickly

as acrylic, or as slowly as oil, but, had many of the properties found

in the oil medium. Alkyd was introduced during this period by Winsor

& Newton, one of the world's leading manufacturers of artist's materials.

I remember going to a presentation by the president of that firm, and

learning about alkyds for the first time. Impressed with the advantages

of the new medium, I immediately began to use it in my paintings. As

one of the first artists to try alkyd, I also contacted the manufacturer

and began testing various formulas of the medium. Recently, the entire

alkyd line was upgraded, and I will attempt to describe the changes.

The unique advantage of alkyd is the drying time. Alkyd remains workable,

and removable, during the course of a day when you are normally working

on a painting. Another quality of alkyd that I consistently use in my

own painting is the ability to quickly build up multiple glazes to achieve

the illusion of great depth. This is possible because the paint you

have applied the previous day is usually dry the next day, particularly

the thin glazes. I will often use 20 to 30 glazes in my skies and water.

Glazes are also of use in getting an intensity of color by glazing one

color over another color, such as a red glaze over a yellow. Additionally,

they can be used to achieve minute variances of tone, and the softening

of edges. I use Liquin as a medium for my glazing. A good example of

this glazing is the background area of Fishing The Ausable, where I

used multiple glazes to make the area behind the fisherman recede into

the atmosphere.

Winsor & Newton has recently upgraded it's older line of 42 Griffin

Alkyds, and now offers 51 colors. Thirty-two of these colors are unchanged,

three have been modified to a brighter hue which is more lighfast, sixteen

colors are new and seven have been discontinued (of which, some were

replaced by lighfast versions or equivalent colors ). In using the updated

line, I was pleased to find the discontinued Alizarin Crimson has now

been replaced by Permanent Alizarin Crimson, and Sap Green has

been replaced by Permanent Sap Green. I use these colors in all my painting

and was happy to know they are now less susceptible to light. In fact,

all colors in the line now carry a permanence rating of AA or A. In

the case of Permanent Sap Green, I notice it now dries faster than the

previous Sap Green.

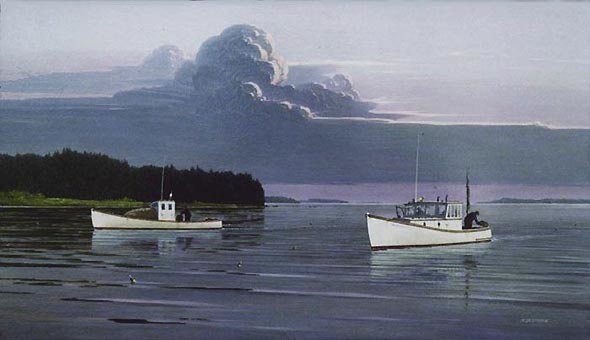

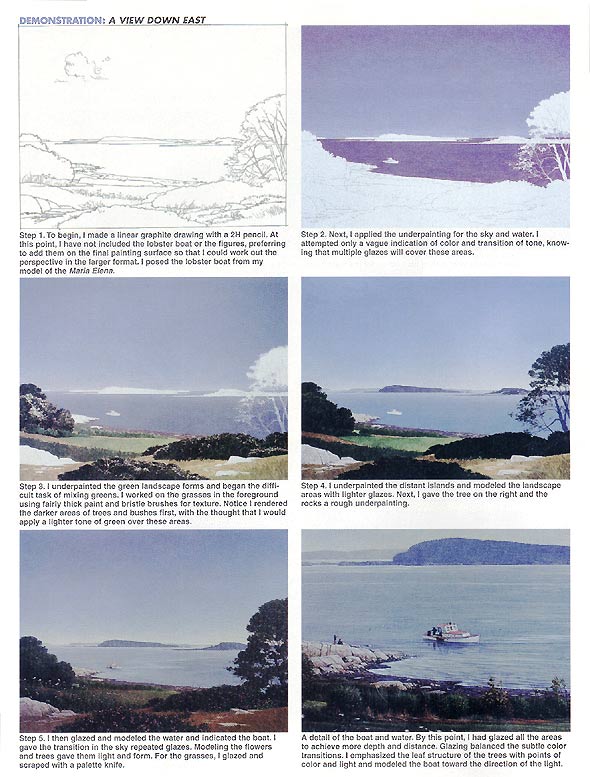

A View Down East was painted for the Modern Marine Masters exhibition, and is the result of some of my experiences in the Jonesport, Beal's Island area of Northern coastal Maine. I am very interested in traditional working boats of the Atlantic Coast, and find the Maine lobster boat a particularly beautiful example of a working boat built of wood. The most beautiful boats of this type are built in the Jonesport-Beal's Island area. Unfortunately, many of the old wooden boats are disappearing in favor of the less distinctive fiberglass boats. In my marine paintings, I will often work from models of these boats. Such models are particularly helpful because you can place them in attitude that would be difficult or impossible with an actual boat. Also, my paintings are usually done at my home in North Carolina, far from the Northern coast of Maine. However, a problem soon arose in the attempt to build models of these boats. After much research, I discovered that the lines plans of these lobster boats are generally not available. I have had to draw my own plans from actual boats I have found dry-docked in Maine. In the accompanying photograph, you see me holding a model of the Maria Elena, an actual boat I found at Great Wass Island, Maine. The same model was posed for A View Down East, and Maria Elena Off The Rocks. Such models are particularly helpful in a rough water painting such as, Pounding Off Beal's Island or Caught In The Surge Off Great Wass, because the boats are in such unnatural attitudes.

The panoramic view in A View Down East is very

similar to an actual view near Jonesport, Maine. However, I have changed

the foreground composition, put a large tree on the right and removed

a dock on the left which was replaced by rocks. The lobster boat was

put into a position off the rocks, and the lobster man is depicted talking

to two children on the rocks. These figures are no more than 1/4Ó high.

The background view of the islands is very similar to the actual view

at Jonesport, and the cloud is used as a compositional element.

My paintings proceed in the usual manner with underpainting and the buildup of basic form. Probably where my work differs the most is in my use of multiple glazes to achieve depth. Again, I will often use 20 to 30 glazes in areas such as sky and water. In A View Down East, this glazing is used to great effect in making the islands recede into the distance by glazing over them with glazes which contain the color found very near the horizon. The glazes usually differ minutely in a color sense. I am trying to get a vibrance with cool versus warm tones, and I often play them against each other. The theory is that light penetrates these multiple glazes and bounces back from the base surface of the painting toward the eye of the observer. This gives the illusion of great depth and is roughly similar to light penetrating a stained glass window. The alkyd medium is about as ideal as I have found to capture this effect without waiting days for these glazes to dry before applying the next glaze. A View Down East took over four months to complete.

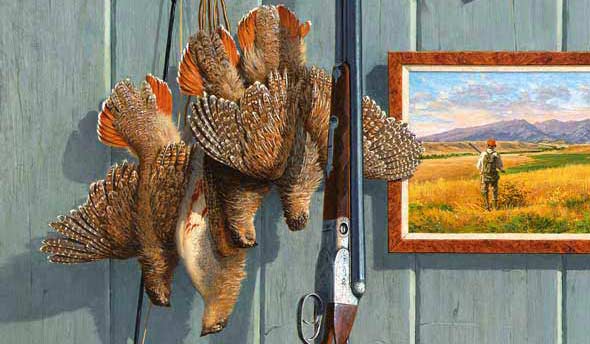

The Crazy Mountains, was the result of a commission. Normally, I do

not accept many commissions, but, when presented with the opportunity

to fly to Montana to fly fish and hunt, I quickly accepted the project.

I have long enjoyed the outdoor life, and one of my true passions is

fly fishing. Also, the commission came from one of my very good friends

who for several years had told me of his experiences in Montana, and

how beautiful the country was in this particular area. He also told

me to get some nice boots and break them in thoroughly as we would cover

alot of ground walking, and rattlesnakes were known to be in the area.

Interesting! Fine! I have no fear of snakes, and some of the largest

rattlesnakes are found where I live in North Carolina. So, three of

us flew out to Montana...two hunters and an artist...it is fascinating

where painting will lead you! It lead us to Big Timber, Montana and

hunting on the Bozeman Trail. You can still see the ruts caused by the

wagon wheels, and the buffalo wallows cleared from the grasslands. Wildlife

abounds, and the Crazy Mountains watch over the scene like a distant

sentinel. With the guide, I followed the hunters in their pursuit of

Hungarian Partridge. I studied the birds and made notes and photos of

their plumage which varied from bird to bird, and I acquired a small

collection of feathers. We covered alot of ground walking...I did not

see a rattlesnake, but I saw alot of major blisters on my feet. My admiration

for the pioneers on the Bozeman Trail took on new meaning, and I sympathized

with the poor pioneer woman who crazily left the wagon train when she

saw those mountains ahead that were named for her. She was never seen

again. On the third day, we decided to try our hand at fly fishing on

the Bolder River in the Gallatin National Forest. We drove up a narrow

road that paralleled the river through some of the most magnificent

mountains I have seen. Stopping at a particularly beautiful passage

of the river, we rigged our fly rods. As I walked to the river, I was

confronted by a sign which read, " Caution! This is an active Grizzly

Bear area." We do not have Grizzly Bears in North Carolina, and

this gave new meaning to the word, "apprehensive" as I tied

on a beautiful Trude dry fly. Thankfully, we never saw a Grizzly, but

I caught some stunningly beautiful cutthroat trout and released them.

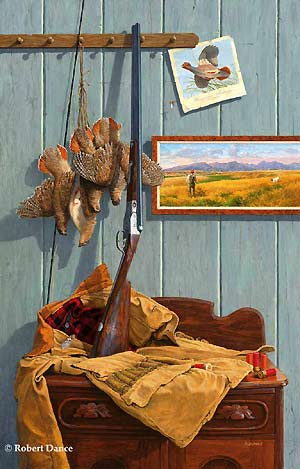

I went through my usual process of sketches and arrived at a pencil

drawing composed of the various elements I thought would tell the story

of our trip. Then, I borrowed the client's very valuable engraved Parker

shotgun and placed it into a final toned sketch for his approval. The

shotgun sits on his hunting jacket with the barrel resting on a coat

rack. The coat rack actually was not there and is completely a made-up

element of the composition. The small antique nightstand at the bottom

has been in my family for years and seemed a good choice because of

it's combination of interesting curves. I thought this would break-up

the rather Mondrian-like composition of straight lines. The painting

within a painting on the wall records the area where we hunted, and

depicts my friend with a pointer dog pointing a covey of Hungarian Partridge.

My friend carries his Parker shotgun shown to the left of the painting.

In the background, you see the Crazy Mountains in much the same way

the unfortunate pioneer woman saw them when she wandered off into the

wilderness. To depict the fly fishing portion of the trip, I used my

own graphite fly rod. Just above the framed painting, you can see the

same Trude dry fly that I tied on while worrying about the Grizzly Bears.

The Hungarian Partridge shown are taken from several different photos

of the birds that I made during the hunt. I placed them together in

an arrangement I thought suitable, and changed the direction of the

light falling on them. From my collection of feathers, I placed a single

feather on the lapel of the jacket. Since these were dead birds, I wanted

to somehow show a live bird, and decided to use the device of an old

print. This print is completely made up from imagination and research

gathered on the trip. The script writing beneath the print, and the

engraving on the shotgun were among the more difficult items to

suggest in the painting.

To those who would like to try a different medium, I would urge you to give alkyd your consideration. The new upgraded line of 51 colors give the painter an increased selection from which to choose. It has stood the test of twenty-three years for me, and I consider alkyd and watercolor my major two means of expression.

In summation, I would encourage painters to follow their interests and thoroughly research their subject. My particular interest is in realism, and I feel there are no "tricks" in this type of realistic painting. It is based on the ability to draw and the careful observation of the natural world with itĚs atmosphere, form, shadow, reflected light, and a myriad of elements to fascinate the careful observer. Realism is the study of nature. Nothing is more vital or more interesting than nature. Portions of this article appeared in American Artist Magazine. |

The

Crazy Mountains, 2000, alkyd on masonite

The

Crazy Mountains, 2000, alkyd on masonite