East

of Swansboro, 1979, alkyd, 20 X 13. This

scene near the coastal town of Swansboro is a study of land, water, cloud

and sky as they recede into the far distance. A number of glazes (20-30)

were used in this painting to imitate the effect of atmosphere on near

and distant objects.

The

idea of trying to paint space and air will impress many as a nebulous

exercise at best, and I must admit that I feel it is one of the more

difficult aspects of painting. However, air exists as surely as

a rock or a figure , and its constant state of change affects the objects

we see both near and far. When looking at the work of the better

realist painters, one can almost stroll through their paintings and

breathe the air. Perhaps it is this seeming ability to walk into

these paintings that leads one to remember them as larger in size than

they actually are. I don't mean to imply that the air in the paintings

seem breathable because the works are so detailed and "magically" real.

I feel the quality of air in a painting has little to do with tightness

of technique. One can see good examples of paintings that seem

full of air in the works of the Impressionists whose use of the vibrant

color can be studied and applied to realism. The

idea of trying to paint space and air will impress many as a nebulous

exercise at best, and I must admit that I feel it is one of the more

difficult aspects of painting. However, air exists as surely as

a rock or a figure , and its constant state of change affects the objects

we see both near and far. When looking at the work of the better

realist painters, one can almost stroll through their paintings and

breathe the air. Perhaps it is this seeming ability to walk into

these paintings that leads one to remember them as larger in size than

they actually are. I don't mean to imply that the air in the paintings

seem breathable because the works are so detailed and "magically" real.

I feel the quality of air in a painting has little to do with tightness

of technique. One can see good examples of paintings that seem

full of air in the works of the Impressionists whose use of the vibrant

color can be studied and applied to realism.

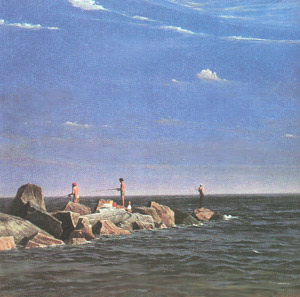

Blues off Fort Macon, 1981, alkyd, 24 X 24. My

sons and I have fished many times from this jetty at Fort Macon, near

Morehead City, North Carolina. The title refers to both the bluefish

the fisherman are catching and the blue sky and water. The line of the

ocean on the horizon is not a hard edge but a hazed one, achieved by

scumbling and glazing. Had this been painted as a hard edge, it would

not tend to recede into the distance.

Blues off Fort Macon, 1981, alkyd, 24 X 24. My

sons and I have fished many times from this jetty at Fort Macon, near

Morehead City, North Carolina. The title refers to both the bluefish

the fisherman are catching and the blue sky and water. The line of the

ocean on the horizon is not a hard edge but a hazed one, achieved by

scumbling and glazing. Had this been painted as a hard edge, it would

not tend to recede into the distance.

To

be able to render atmospheric effects, perhaps one should know the air's

chemical makeup. However, I have always felt that too much dependence

on the scientific or mechanical aspects of art (such as mechanical perspective)

has a tendency to draw the life from art. Proper understanding

of such subjects is essential, but after one knows the facts behind

what is happening, it may be best to relegate that understanding to

the subconscious and think more about art. To

be able to render atmospheric effects, perhaps one should know the air's

chemical makeup. However, I have always felt that too much dependence

on the scientific or mechanical aspects of art (such as mechanical perspective)

has a tendency to draw the life from art. Proper understanding

of such subjects is essential, but after one knows the facts behind

what is happening, it may be best to relegate that understanding to

the subconscious and think more about art.

Air

consists of 78 percent nitrogen, 21 percent oxygen, 9 percent argon,

.03 percent carbon dioxide, traces of other gases, and a variable load

of water vapor. Air molecules intercept the short blue wavelengths

of the sun's radiation, thereby giving us our blue skies. The

lighter value of blue at the horizon is caused by light rays penetrating

a longer distance through dense lower air which contains water vapor,

dust, and varied gases. This effect often appears to have tints

of vermilion or alizarin crimson near the horizon. It is the water

vapor, plus varied particles of dust and smoke that affects the landscape

as we see it.

The

effect of air on a landscape will obviously change with each minute,

day, and season. A humid day will find the air filled with minute

particles of water vapor. An extreme example of this would be

a dense fog, but this vapor can be seen on almost any day when viewing

distant landscapes. These particles of water vapor combine with

dust and tend to blur our vision of distant objects. They also

give distant objects a bluish or purplish cast and flatten their three-dimensional

quality. A good example would be a distant view of a mountain

range or islands off the coast of Maine which would tend to look flat

as in a stage set. This effect can be exaggerated as seen in many

watercolorists' backgrounds done with flat washes of granular color. The

effect of air on a landscape will obviously change with each minute,

day, and season. A humid day will find the air filled with minute

particles of water vapor. An extreme example of this would be

a dense fog, but this vapor can be seen on almost any day when viewing

distant landscapes. These particles of water vapor combine with

dust and tend to blur our vision of distant objects. They also

give distant objects a bluish or purplish cast and flatten their three-dimensional

quality. A good example would be a distant view of a mountain

range or islands off the coast of Maine which would tend to look flat

as in a stage set. This effect can be exaggerated as seen in many

watercolorists' backgrounds done with flat washes of granular color.

Snow

at Currituck, 1979, alkyd, 35 X 48. A

scene on the coastal sounds of North Carolina. Note how the land mass

loses definition to the right of the painting and in the extreme distance

at the center of the painting. Also, the wave action is more clearly

defined in the near distance than it is toward the bottom.

As

we look through this layer of air, the objects closest to us will naturally

be seen with sharpness and clarity. But as objects recede, this layer

of atmosphere begins to haze the edges of distant objects. The

shapes seen to melt into the distant atmosphere. During the day,

this effect will change according to the dictates of temperature, humidity,

light, and wind-blown dust or smoke. Also to be considered is

the eye's focusing ability. When focused on nearby objects, the

eye loses its ability to focus on distant objects. This also results

in the illusion of depth. The paintings of the Luminists Frederic

Edwin Church or John Frederick Kensett clearly depict those phenomena.

Winslow Homer's The Artist's Studio in an Afternoon Fog and Thomas Eakins's

A Pair-oared Shell show these effects on background objects. As

we look through this layer of air, the objects closest to us will naturally

be seen with sharpness and clarity. But as objects recede, this layer

of atmosphere begins to haze the edges of distant objects. The

shapes seen to melt into the distant atmosphere. During the day,

this effect will change according to the dictates of temperature, humidity,

light, and wind-blown dust or smoke. Also to be considered is

the eye's focusing ability. When focused on nearby objects, the

eye loses its ability to focus on distant objects. This also results

in the illusion of depth. The paintings of the Luminists Frederic

Edwin Church or John Frederick Kensett clearly depict those phenomena.

Winslow Homer's The Artist's Studio in an Afternoon Fog and Thomas Eakins's

A Pair-oared Shell show these effects on background objects.

This

haze-like atmosphere can be rendered through the use of multiple transparent

or translucent glazes which imitate the actual haze found in nature.

Just as the real atmosphere mutes color and blurs edges, an applied

glaze can do the same in a painting. I have found that the addition

of a bit of white in the glaze will imitate the effect of the vapor

particles in the air. Thus, the underpainting should be a few

values darker than the final value desired. An atmospheric glaze might

consist of a bit of white, cobalt, and ochre ( I use alkyd paints) and

a good deal of medium ( in my case, Liquin). This mixture will

vary in color selection and transparency according to the effect desired.

Through this type of glazing, the value and color of distant objects

can be controlled in the most subtle of gradations. However, a

similar effect can also be accomplished by careful color and value selection

of opaque paint while trying to compensate for slight darkening or lightening

as the color dries. I personally feel that opaque color cannot

carry the same sense of depth seen in a glaze.

Cape

Lookout Morning , 1979, alkyd, 33 1/2 X 48. This

lighthouse, which has been standing since 1859, is one of the distinctive

landmarks along the outerbanks of North Carolina. A vibrancy is given

to the bluish-gray low-lying cloud mass by applying strokes of warm

and cool glazes in a subtle use of the Impressionists' technique. This

technique is more noticeable toward the right horizon where strokes

of a warm glaze made up of ochre and white are played against a cool

glaze of colbalt and white.

Shadows

and reflected light also play a large part in creating the feeling of

air in a painting. In fact, a painting may seem devoid of air

until shadows are painted. A sense of three-dimensional space

can be achieved through the use of reflected light on objects. Shadows

and reflected light also play a large part in creating the feeling of

air in a painting. In fact, a painting may seem devoid of air

until shadows are painted. A sense of three-dimensional space

can be achieved through the use of reflected light on objects.

We

can learn how to imbue the air with a luminous quality by studying the

techniques of the Impressionists. The vibrant use of subtle strokes

of warm and cool color in sky areas will give the feeling of depth in

a sky. I will often apply stokes of warm and cool glazes over

a blue sky underpainting to achieve a vibrancy, particularly toward

the horizon as the sky lightens. The technique as I use it is

not as obvious as that used by the true Impressionist, but it is still

there.

A demonstration

of how I painted Columbus, Georgia appears below. This landscape

was commissioned by the W.C. Bradley Company of Columbus, Georgia.

I was free to select the subject matter for this painting and ended

up choosing a view of Columbus from a bridge over the Chattahoochee

River. On a very hot day, I did some pencil drawings from the

bridge and took a few color photographs to give me an idea of general

color. I feel that the color found in photographs is not the kind

of color I see, but it can give me an approximation in a subject as

involved as this painting.

The actual painting was done in my studio and measures 18" x 40".

I have often painted seascapes, and I was able to paint water again

in this subject by using the river ( which was quite low) as a major

element. You will notice that the eye is led into the distance

by the river itself and by form overlapping other forms. As these

forms overlap, they lose value, color intensity, and edges owing to

the humid air and haze. The extreme distance visible would be

represented by the hazy set-like line of trees beyond the distant bridge.

This line of trees and a few forms closer do not really have edges but

"melt" into the atmosphere surrounding them. The closer subjects

are fairly hard-edged, (showing) the figures exploring the river.

On

the day following my pencil drawing of this scene, there was a very

hard rain and the sandy islands in the river disappeared beneath the

water. I was pleased I had drawn the islands, as I feel they help

lead the eye into the painting and give a needed note of warm color.

Also, the figures could not have been included had the river been high.

The attempt to paint space and air into a painting can be a challenge

that summons up all one has learned about rendering perspective, form,

color, and edges. The greatest help, of course, is the careful

observation of nature itself and the awareness of how amazingly different

outdoor scenes can look over a 12-hour period.

DEMONSTRATION:

'COLUMBUS,

GEORGIA' DEMONSTRATION:

'COLUMBUS,

GEORGIA'

STEP ONE: Initially,

a detailed drawing was made from a bridge overlooking the city of Columbus,

Georgia. Then, a simple outline drawing was done on a gessoed panel

of untempered Masonite. This was followed by the first stage of underpainting

with rough-in of the tree forms, water, sky and clouds.

STEP TWO:

The basic underpainting. Some areas, such as the distant forms, were painted

a few values too dark, since I planned to paint over them with lighter

glazes which would represent atmospheric haze.

STEP THREE: I

continued working on the buildings and water tower structure; glazes were

applied to the background trees beyond the bridge.

STEP FOUR: The

transition of blues from dark at the top to a lighter blue toward the

horizon was done by glazing over darker values in the underpainting.

As the glazes approached the bottom horizon, more white was added to

the glaze to achieve a lighter value. In this manner, very subtle values

in the transition from dark to light could be precisely controlled.

STEP

FIVE: The

completed painting: Columbus, Georgia, 1984, alkyd, 18 X 40. Click anywhere

on the painting above for a enlarged, detailed view.

Robert

B. Dance was born in Tokyo, Japan, and lives in Kinston, North Carolina,

with his wife Coleman. He is a graduate of the Philadelphia College

of Art where he studied under Henry C. Pitz.

Dance

is noted for his landscapes and seascapes, and his work has appeared

in American Artist on several occasions. His paintings have also

appeared in art publications here and abroad and in the following books:

40 Watercolorists and How They Work, Painting in Alkyd (both published

by Watson-Guptill Publications), and Things Invisible to See ( Advocate

Publishing Group). The North Carolina Watercolor Society has awarded

his work first prize in three different exhibitions.

His

work is in numerous corporate and private collections, including those

of the Northern Carolina Museum of Art, The Southeastern Center for

Contemporary Art has shown his work in several realist invitationals

and his work was included in the exhibit "Southern Realism," organized

bye the Mississippi Museum or Art.

Dance

has also tested new formula pigments for Winsor & Newton and has

been shown in their international presentation on alkyd pigments.

|